"The New Testament is full of Jew-hatred. From its negative depiction of the Pharisees to its charge of 'Christ-killing', it's been THE major cause anti-Semitism for 2000 years!"

This is a view usually not stated openly, but is unfortunately, widely believed by many Jewish people. We at CHAIM Ministry (www.chaim.org) have heard this argument more than a few times. If someone said this to you and you were a Christian, how would you respond?

Your Jewish friend may like you as a person. He may even respect Christianity in general. But this view of the New Testament is still widespread: that the troubles between Church and Synagogue can largely be traced to the New Testament.

Now this isn't just a "Jewish" problem. This bias towards the New Testament and the gospel it contains is shared by many Muslims too. But we need not go too far afield, here: I even speak to a lot of Roman Catholics who assure me that their years in Catholic school have given them "all the religion they need" for the rest of their lives. But when I ask them what the gospel is, what comes out of their mouths is "duty", "obligation", "going to Mass", "church attendance", "being good Catholics." I talk to enough African-Americans (and Caucasians!); of people who grew up in a gospel culture, and for plenty of them, when they tell me what the New Testament's gospel is, what they say is pretty much the Protestant version of what the Catholics say: the need for works, performance, duty, "my good deeds outweigh my bad deeds". For well over half of them, what they say has nothing to do with the essential message of the New Testament: what Christ did on the Cross. Rather, what they say has everything to do with them and their religious performance (or lack of it): in essence, a definite negative presumption about the New Testament and the message it contains. Historically, Jews have harbored those negative presumptions too, and their history in Europe helps us to understand why.

The Promised Land, published in 1912, was an autobiographical sketch of author Mary Antin's childhood life in Czarist Russia and her subsequent coming to America during one of the worst pogroms in history. A "pogrom" (Russian: "to wreak havoc") was a government-initiated riot against Jews in lands under Czarist rule. One of the worst pogrom was in 1881, the year Antin and many thousands of other Jews emigrated to the United States. During the pogroms, both Britain and America issued formal protests to the Russian government. In Promised Land, Antin shares the terror she experienced as small girl, hiding with her parents in her own home while marauding bands of churchgoers marched through the streets, stirred up by government-sponsored priests of the Orthodox church against the "Killers of Christ" living in their midst. The mobs believed they were expressing their love of Jesus by their hatred of the Jews. What's significant here is that Czarist anti-Semitism was distinctly religious. Antin explains that Christmas and Easter were especial times of terror for the Jews in the Pale of Settlements: those areas especially designated for Jews to live. Consequently, these late 19th Century emigres passed on to their children and grand-children their experiences of what it was like when "Christians" left their Easter and Christmas church services in Czarist Russia.

No wonder the New Testament is not a favorite book among Jews today, not for what's actually written in it, but for what kind of people presumed to represent its message! Roughly half of today's American Jews had grandparents and great-grandparents who left Czarist Russia during that time, a time in history popularized by the play and then the movie "Fiddler on the Roof."

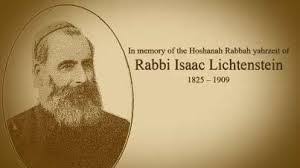

The first Czarist pogrom is usually dated from 1821, but Russia wasn't the only country that had anti-Jewish riots in the name of Christianity. In neighboring Tisza, Hungary, (across the border) the district rabbi Isaac Lichtenstein (1824-1908) ministered to his congregation during the infamous "Tisza Eslar Affair", when leading Jews there were falsely accused of murdering a Christian girl and using her blood in a ritual. This baseless slander was eventually exposed due in part to the efforts of famed Bible scholar Prof. Franz Delitzsch of the University of Leipzig. (Keil and Delitzsch's Commentary on the Old Testament: 10 Volumes), but the resulting anti-Jewish rioting so vexed Rabbi Lichtenstein that he decided to read a New Testament in order to discover a basis for all this hatred. This was the same New Testament copy he had read in anger 40 years before and hurled into a corner of his study where it remained untouched until the day he read it again after this riot. But what he found in it was the opposite of what he thought he'd find. He writes ...

"I had thought the New Testament to be impure, a source of pride, of selfishness, of hatred, and of the worst kind of violence, but as I opened it, I felt myself peculiarly and wonderfully taken possession of. A sudden glory, a light flashed through my soul. I looked for thorns and found roses; I discovered pearls instead of pebbles; instead of hatred, love ..."

"From every line in the New Testament, from every word, the Jewish spirit streamed forth light, life, power, endurance, faith, hope, love, charity, limitless and indestructible faith in God ..."

Lichtenstein started using the New Testament in his synagogue preaching until three years later, he confessed to his congregation that he had been doing this, and that he'd become convinced that Jesus of Nazareth was Lord and Messiah. His conversion became known, to the astonishment of all the Jewish communities of Hungary. Lichtenstein published three pamphlets telling of his new-found faith. When he was called before the Chief Rabbi of Budapest to recant his views, he refused. His fellow-rabbis asked him to resign and be baptized but he refused, replying that he would not join a church or be baptized, but that he only desired to stay with his congregation. His congregation voted to have him stay as their "Christian" rabbi. Finally however, he did resign and continued a writing and visitation ministry across Europe, hounded by his fellow-rabbis but supported by several missionary organizations.

"When the roll is called up yonder" as the old hymn goes, there no doubt will be many obscure saints honored whom most of us have never heard of here on earth. Their fame will have to wait for that glorious day. And for that reason, Rabbi Isaac Lichtenstein is one of the "Honorable Menshen".

("Menshen": plural for "mensh", which is Yiddish for "a person deserving of honor".

[sources:]

1) Wikipedia

2) The Promised Land, Mary Antin, 1912

3) The Anguish of the Jews, Edw. H. Flannery, Paulist Press

4) Famous Hebrew-Christians, Jacob Gartenhaus (as quoted by: Answering Jewish Objections to Jesus - Vol. 1, Michael L. Brown, Baker Books, 2001

5) "The Story of Rabbi Isaac Lichtenstein", http://www.messianicassociation.org/bio-lichtenstein.htm

6) Answering Jewish Objections to Jesus - Vol. 1, Michael L. Brown, Baker Books, 2001